|

|||||||||||||||

|

My blog discusses the important and complex subjects of college completion, college success, student risk factors (for failing), college readiness, and academic preparation. I will explore the pieces of the college puzzle that heavily influence, if not determine, college success rates.

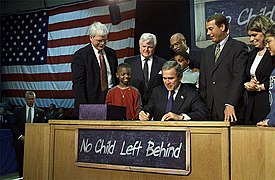

No Child Left Behind Discourages State College Prepardness: Guest Blogger- Go College

This past week, a Boston Globe article revealed the development of an alarming educational trend within the State of Massachusetts. Hidden beneath the surface was yet another subtle demonstration as to why the No Child Left Behind Act may actually be acting as a deterrent to improved educational outcomes.

The issue? It seems that many Massachusetts high school graduates are unprepared for college. In fact, literally thousands of college students are forced to take remedial classes when they begin their college studies. What makes the issue so worrisome for experts is that students who do take remedial classes are far more likely to drop out of college. Statewide Study The issue was far worse for urban school graduates. Roughly 70 percent of students from at least three high schools in Boston and two in Worcester had to take remedial classes upon entering college. One surprising aspect of the study conducted jointly by the state Departments of Elementary and Secondary Education and Higher Education was that the problem was independent of socioeconomic status. In an unusual development for education, many suburban school districts had similar numbers to those of less affluent schools. When it came to the community college network, roughly two-thirds of the 8,500 students enrolling took a remedial course. According to college administrators, that factor is one of the reasons that the drop out rate at the state’s two-year schools is so high.

The MCAS Requirement In discussing that development with the Boston Globe, Robert Gaudet, an education researcher at the University of Massachusetts’ Donahue Institute, offered the following assessment. “The dirty little secret is that MCAS doesn’t test 10th grade skills, much less college skills. Passing is not that hard, it’s getting to proficient that’s tougher.” It is at this point we come to the law known as NCLB and the subsequent definition of the term proficiency. Many would like to see proficiency under NCLB defined as college readiness - in fact the law appears to suggest just such a level. If that were in fact the case, then theoretically the next step would be to raise the test standards so that passing the MCAS meant a student was in fact ready for college level work. But taking such a step would bring one of the major absurdities of the law into play, the demand for 100% proficiency. Raising test standards would guarantee that every Massachusetts High School would fail to make the federal guidelines for Adequate Yearly Progress under the law. Because of that potential development, it is our guess that the test standards will not be raised to such a level. In essence, NCLB, with its extreme punitive structure and absurd goals, will act as a deterrent to taking steps to raise educational standards. Proficiency Versus Basic Skills Instead, those researchers suggest that two options exist - standards can either be minimal, thereby presenting little in the way of challenge to typical students or they can be rigorous and challenging, and ultimately unattainable by below average students. Given that backdrop, it is easy to see the confusion developing. It is precisely the situation the Massachusetts study revealed. The MCAS is a basic skills test, not a college readiness exam, and therefore meaningless in regards to the Massachusetts issue. In fact, that is precisely what one would expect given NCLB’s insidious punitive nature and unrealistic expectations.

In Massachusetts, folks are working hard to raise standards. State education officials unanimously approved a core high school curriculum in November, a recommended program that includes four years of English, four years of math, three years of science, and three years of history. However, it must be noted that not all of our students will be able to handle college level rigor no matter how hard educators work. In spite of that fact, we continue to assume that college-ready is possible for every single student. It is time for America to realize it is not. As we have noted previously, one necessary step in this educational dilemma is to promote a vocational option, a hands-on, less academic approach that focuses on career options. Such a program must be available well before the end of high school, perhaps as early as ninth grade. Unfortunately, such training is thought of as second class in the US while college is thought of as first class. But if the goal is to create students who are ready to be positive contributors to society, then they first must be able to make a good living. We agree. It is a step that other countries have used very successfully. Murray also indicates that far too many people place a premium on a college degree. Yes, many careers/jobs demand such a degree as its qualification. But many more careers are available with two years of specific training. Here in Maine we continue along the opposite path. Our education promos feature slogans such as “College for ME” and “Everyone College Ready”. The goal is noble, trying to ensure that kids have options after high school is a great premise. But such slogans further foster that negative viewpoint of vocational education/training. If we continue to state that going to college is the best answer then there is no option for our kids but to see vocational education/training as second class. Back to Massachusetts Because some additional students will be unable to meet those higher standards, those students will give up on the system. In our eyes, raising educational standards will exacerbate the current drop out problem. Only when raising standards is discussed against a back drop of creating meaningful options for students who cannot handle the academic rigor associated with college level work will we be able to increase expectations without increasing our drop out rates. Despite proponents spin on the law, NCLB fails to address this fundamental dilemma. In fact, it likely prevents school districts from taking the steps to increase standards because increasing standards will only bring about more penalties for schools. And because the law governs the actions of our public schools, we have situations like that of Massachusetts, where 100% proficiency goals get confused with the goal of college readiness, and students are caught in the absurdity of it all.  Labels: academic preparation, Student Success |

2 comments

We are forcing round pegs into square holes. During my 5 years of teaching mostly low level students it is clear to me that most students can perform rigorously but it takes them more time. And they don”t need 4 years of math to succeed in life, especially if they’re not going to college to study math or science or engineering.

You are exactly correct that one of the insidious effects of NCLB is increased disrespect and non-support for the folks (to quote Mike Rowe) who do the dirty jobs that make civilized life possible for the rest of us.

The notion that plumbing, welding, and other blue-collar jobs are just what someone “settles for” when they aren’t “good enough” for college is an insult to all the people who keep the country functioning.

And creating a one-size-fits-all educational system that does not meet their needs only makes them more likely to walk away from educational institutions with even less education than they might otherwise have obtained.

It is not simply that schools need higher standards– it’s that we need a variety of standards that suit the needs, abilities, and career paths that our many and varied students will follow. But under NCLB, schools do not exist to meet the needs of the students– students must be trained to meet the needs of the school.

Leave a Comment